Sixteen actors, most in bare feet, encircle a chair, telephone and chaise lounge. Vaishnavi Suryaprakash is wearing a black T-shirt and rolled up floral pants. With a sticky-noted script in hand, she is rehearsing as 22-year-old Radha, who – at this point in the play – is at her grandparents’ home in Colombo, Sri Lanka, in 1977.

In this scene, being crafted in a warehouse in Sydney’s Surry Hills, Radha is refusing to marry a man for the benefit of family alliances, and fervently warns of the country’s coming descent into violence and terror. “Everyone is so busy forming their own united fronts that the country itself is united about precisely nothing,” she insists.

The tension builds until family matriarch Aacha (Sukania Venugopal) slaps Radha, accusing her of “shouting out whatever thoughts come into your bloody head”.

When I first meet the cast and crew it is mid-December, and a month until Counting and Cracking will premiere at Sydney Town Hall. This story of identity and secrets, of refugees and humanity, is a grand narrative spanning four generations and 50 characters; it’s also Belvoir Street theatre’s most ambitious undertaking in its 35-year history, as epic and Australian as Cloudstreet or The Secret River.

The play rotates through four eras – 1957 in Colombo, when Radha is an infant; 1977 again in Colombo, when oppression is a harbinger of the civil war to come; 1983, when it finally makes its bloody arrival; and 2004 in western Sydney, where Radha’s past never seems completely left behind.

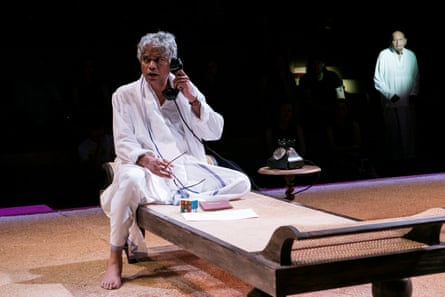

During performances, Radha’s grandfather – Tamil politician Apah (Prakash Belawadi) – will be chained to an armchair for creating a “public disturbance”; Sri Lanka, he says, will be torn in two by efforts to make Sinhala the country’s sole official tongue, while suppressing the Tamil language.

Apah wants equality between Tamil, Sinhalese and Burgher, but was taught early that democracy is “the counting of heads, within certain limits, and the cracking of heads beyond those limits”.

The scene breaks. Director Eamon Flack questions how this family argument is playing: “I feel like a politically incendiary statement is never met with silence.” But the play’s creator, S. Shakthidharan, known as Shakthi, disagrees, insisting the debate here is not incendiary. He understands these fraught family arguments through his own experience.

Shakthi describes himself as an “Australian storyteller with Sri Lankan heritage and Tamil ancestry”; his own family fled Sri Lanka in 1983. He began writing Counting and Cracking as a means to gather more details about his family’s history: he spent four years listening to a couple of hundred relatives tell their version of events, eventually deciding his play should not take sides but be a “space for many truths”.

The character of Apah, the politician, was inspired by Shakthi’s great-grandfather. “The overall piece is a work of fiction, but everything in it comes from something real in one of those interviews or conversations,” he says. The creative task is to not take sides. “It’s less important to be right than it is to listen.”

Shakthi’s mother thought this play was a “really stupid idea” but, having read the first draft, she began coming to workshops. “Slowly she opened up to talking about Sri Lanka. A lot of what she said has ended up in the play,” he says. Much of this reticence is generational, an unwillingness to discuss traumas of life in war-torn Sri Lanka, but this has left second- and third-generations such as Shakthi with gaps in their understanding of family history.

Three days before opening night, a preview performance in Sydney Town Hall is sold out. Audience members are treated to spicy lamb biriyani or chick pea and eggplant curry in the foyer, then make their way into purpose-built wooden stadium seating with cushions that fills most of the hall, surrounding a generous, long stage.

Up high, right off where the actors enter, three musicians provide a live soundtrack that is joyous and rhythmic, sometimes haunting, with instruments including violin, flute, tabla percussion and a long traditional drum.

Young Radha dances in wearing a stunning red and gold sari, a braided hair extension down her back; actor Suryaprakash, who was born in India, was able to draw on her own traditional dancing skills. The ensemble dance in her wake, tossing white flowers from golden pots and woven baskets.

Including the musicians, there are 19 performers who come from six countries, mostly with south Asian heritage – generally India and Sri Lanka – and speak 11 languages between them. “Having so many languages in that room is so beautiful,” says Suryaparakash. “You get such a feeling of place and culture and identity from the rhythms.”

Writer Shakthi believes Tamil is a “really performative” language; one word can have different meanings “depending on the emotion you say it with”. Hence the actors, who sometimes slip into Tamil and Sinhala during the show – which fellow actors beside the stage immediately translate to English – add to the musicality.

In one scene, a 48-year-old version of Radha (Nadie Kammallaweerra) is confronted by a man raising funds for the guerilla organisation the Tamil Tigers (Rajan Velu), who pushes his way inside her Pendle Hill apartment in western Sydney. He aggressively insists Radha’s son Siddhartha (Shiv Palekar), born in Australia, be sent to Sri Lanka to join the armed struggle.

“I’m not Sri Lankan; I’m Australian,” insists Siddhartha, who becomes the focal point of the play’s theme: searching for identity within and between borders. He calls himself “Sid” to fit in.

Palekar, who was born in India and raised in Hong Kong, relates to his character’s quest for home and belonging. “I was in this full existential spiral when I was 21, Siddhartha’s age, just kind of not knowing anything, having no real anchor to a place,” he says. “I’m a foreigner when I go back to India, a foreigner in Hong Kong and a foreigner here.”

Siddhartha comes to understand his place in Australia through his Yolngu girlfriend Lily (Rarriwuy Hick). The character was inspired by a conversation Shakthi had with his erstwhile theatrical collaborator, Yolngu performer Rosealee Pearson, about DNA research that linked south Asians and northern Indigenous peoples of 4,000 years ago.

This country’s cultural origins is woven neatly into the play, along with Australia’s continuing political paranoia over the continent’s borders. Australia’s obligations under the UNHCR’s 1951 Refugee Convention come into play, as one character pleads with another: “Do not get on that boat. People die on those boats.”

Shakthi hopes Counting and Cracking “can help people heal”, encouraging a feeling among his community that “we’re part of the Australian story”. He also hopes that it will gently fill “this silence that exists between first- and second-generation migrants … and that the wisdom of the incredible experiences they went through overseas can be passed on to future generations”.

Counting and Cracking plays Sydney festival until 2 February, before a run at Adelaide festival from 2-9 March.