A man joins the Black Lives Matter demonstration in Melbourne and holds a placard “All lives matter”. It’s snatched from him and the police take him away while he is stating what many of those who have engaged in similar counter-sloganeering have stated before him: “There is nothing racist about this.”

While some veteran white supremacists, hypocritically, are familiar with the kind of blurring of reality that their counter-slogan is creating, other people I know still don’t understand how offensive the proclamation “all lives matter” is. So in the belief that some who genuinely misunderstand what is happening can be made to understand, and because it is useful to what I want to argue, let me explain what to many of us is obvious.

Black Lives Matter is not an answer to an abstract question such as “which lives matter?” In today’s context Black Lives Matter is directed at a racist culture which cheapens the lives of black people. It clearly means “black lives should also matter”. It is an invitation to make visible the specific devalorisation of black lives in our society. That is why responding to Black Lives Matter with “all lives matter” is racist. It tries to make this specific devalorisation invisible.

Racists, as a rule, strive to make you visible when you want to be invisible, and to make you invisible when you wish to be visible. If you’re trying to be one of the crowd, the racists will pull you out of that crowd, throw your difference at you and scream: “How dare you act as if you’re one of the crowd? You are different!” But if you say, “I am being targeted because of my difference,” the same racists will scream at you: “How dare you act as if you are different? You’re just one of the crowd.” The slogan “all lives matter” works precisely in this way: “Let’s make your horrendous experience disappear by talking about ‘all of us’ rather than about you specifically.”

But if for some of us, anti-racist writers and activists, critiquing “all lives matter” is relatively easy, what about the various acts of anti-racist solidarity that we and others engage in and that also end up decentring the black experience?

For instance, while there are plenty of occasions where one can use anti-black racism to reflect on “racism in general”, and while there are also many occasions where one can equate racialised experiences and say, “We Palestinians, or we Holocaust survivors, know what it is like … ,” there are times where such generalisation and equalisation achieve the same effacement of the specificity of anti-black racism as “all lives matter”.

Do logics of generalisation and equalisation such as the above dilute specificity? The answer is not an easy yes or no, in the abstract. The question should invite us to reflect on when it can be a yes and when it can be a no. And there is no doubt that today, amid the Black Lives Matter demonstrations that are happening around the world, to engage in generalisations about “racism”, or in equalising forms of solidarity, is to participate in effacing the specificity and acuteness of anti-black racism.

Anti-black racism is historically one of the most lethal racism there is. No one has to inherit the combined traumatic history of colonialism, slavery and racial exclusion the way black people do. The mere weight of this history has a racialising and chattering effect on those who carry it that is hard for any of us, including other racialised people, to comprehend. At the same time, everywhere around the world, black racism is perpetuated by being articulated to police brutality in a way that no other racism is.

Police brutality inserts itself into the consciousness of a black person in the way the threat of rape inserts itself in the consciousness of women. For many, indeed for most, it is an ever-present danger. A change of a radical nature is required to bring this to an end.

I receive an email from my university telling me that given what is happening in the US “now is the time to think about racism”, and I think: that is not good enough. In my university, we’ve had to deal with the rise of anti-Indian racism, and we’ve had to deal with the rise of anti-Muslim racism. Recently with Covid-19 we had to deal with the rise of anti-Asian racism. All are, of course, important and I am certain that it is good for the university to reflect on how it can think these racisms together to infuse a permanent anti- and non-racist culture on its campuses.

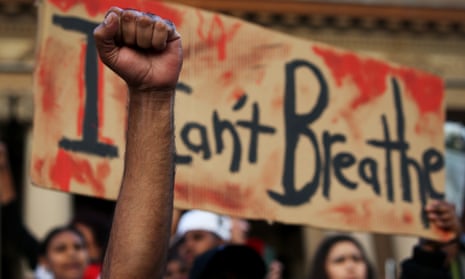

But today, in the face of the traumatic events that black people have had to endure, what is communicated to us by protesters is clear: “Now is the time to think about black people, to think about anti-black racism, and to do something concrete about combating it, particularly in relation to the foundational role of police brutality in perpetuating it.”

That’s what I want my university to reflect on and do something about. Speak to its black students and staff, confront the question of police brutality towards black people inside and outside campuses, and do something concrete to support black students. The same goes for every institution anywhere. The killing of black people, followed by riots and outrage, followed by a return to the same order of things, is a familiar pattern.

Protesters around the world are inviting us to make the slow and horrendous death of George Floyd the start of something different. And it should be easy to tell who is serious about starting the hard work of instituting something different and who will lazily return us back to more of the same.