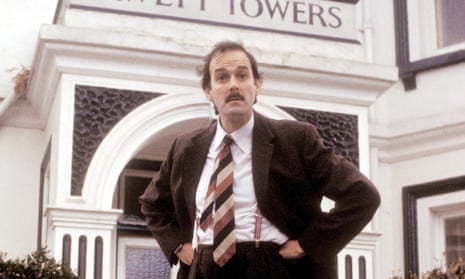

“Some years ago I opined that London was not really an English city any more,” is how John Cleese began a tweet on Wednesday. “Since then, virtually all my friends from abroad have confirmed my observation.” When eight long years ago he made a similar claim, he gave us the unabridged version. “I’m not sure what’s going on in Britain,” he said while appearing on an Australian TV programme. “Let me say this, I don’t know what’s going on in London because London is no longer an English city and that’s how they got the Olympics. They said: ‘We’re the most cosmopolitan city on Earth,’ but it doesn’t feel English.”

Where to start? Maybe with the most obvious point of them all: Cleese is fine with immigration if it’s him moving. It’s plausible that when he sat down to write this tweet, Cleese was in Nevis in the Caribbean. Having had enough of the England he cherishes so much, he announced last year he was planning to move there. The difference is obvious: he bemoans immigrants in London, but because of race and class he’s called an “expat” in the Caribbean.

Now, Cleese claimed his comments are not about race. But back in Australia, he gave more evidence for his argument. “I had a Californian friend come over two months ago, walk down the King’s Road and say to me: ‘Well, where are all the English people?’” Assuming they didn’t ask every single person they saw that day where they were born, how did Cleese’s Californian friend know none of them were English?

You have to wonder what does it mean for London not to be “English”? What does it mean to be an “English city”? Cleese gave us an idea in 2011: “I love being down in Bath,” he said, “because it feels like the England that I grew up in.” Who knows why Cleese feels at home there – is it because the overwhelming majority of the population of that city is white British?

But London, just like England, has always been constituted by global connections. Violent material, wealth and labour extraction from the colonies helped finance the industrial revolution and brought money flowing into the capital.

London and parts of Britain have always been diverse: Irish and Jewish migrants in the 1800s and early 1900s were considered racialised “others”; people from colonies and former colonies, who, after being educated on an English curriculum, came as citizens to work in the “mother country” were met with racism. This is perhaps not the England Cleese had in mind, but it’s the England that has long been. “There is no English history,” the academic Stuart Hall wrote, “without that other history.”

This history and what it means for England’s sense of self is ill understood. Cleese defended his comments by claiming “it’s legitimate to prefer one culture to another”, but there is no such thing as one static “culture” tied to one particular nation.

I think it's legitimate to prefer one culture to another

— John Cleese (@JohnCleese) May 30, 2019

For example, I prefer cultures that do not tolerate female genital mutilation.

Will this will be considered racist by all those who hover, eagerly hoping that someone will offend them - on someone else's behalf, naturally https://t.co/4WbZDFjs3o

But this is not just about Cleese – though that he’s an Oxbridge-educated, wealthy actor is a reminder of just how disingenuous it is for politicians to claim that it’s predominantly the “white working class” or the “left behind” who feel threatened by immigration. Fixating on the individual obscures the structural, and that’s where the real power and the real problem is. This very idea that Cleese is so wedded to – that immigration is making London less English – has been, in different ways, reproduced through the UK’s mainstream debate on immigration and race for decades, if not centuries. Only it’s been applied to the country as a whole, not just London.

The idea that national identity needs to be guarded against culturally different “others” was part of the reason 11 Labour MPs protested against the Empire Windrush docking at Tilbury in 1948. It was connected to Theresa May’s Home Office sending “go home” vans around diverse parts of the country, it’s what William Hague was referring to when he warned of the UK becoming a “foreign land”. It was also central to Tony Blair’s New Labour fixation on Britishness, on to Gordon Brown’s “British jobs for British workers” pledge and Ed Miliband’s 2015 election offer of controls on immigration. The underlying sentiment of Cleese’s comments is part of what politicians mean when they talk about listening and responding to people’s “legitimate concerns” about immigration. Here, perceived culture remains intimately connected to race.

Englishness and Britishness are, in all kinds of subtle ways, still tied to whiteness. The connection is there in the supremacist narratives of the British empire that suggest innate capability meant a country such as England “developed”. It’s detectable in the way certain immigrants and Britons – including people from eastern Europe, who are seen as part of a degraded whiteness – are more likely than others to be imagined as a threat to “British culture”. And it’s painfully obvious when you compare how some people’s Englishness is questioned (think Norman Tebbit’s “cricket test”) while other people’s is absolute.

The problem is far bigger than one comment made by one actor – it’s written into the way race, immigration and nation are understood in popular debate. And that is what we need to change.