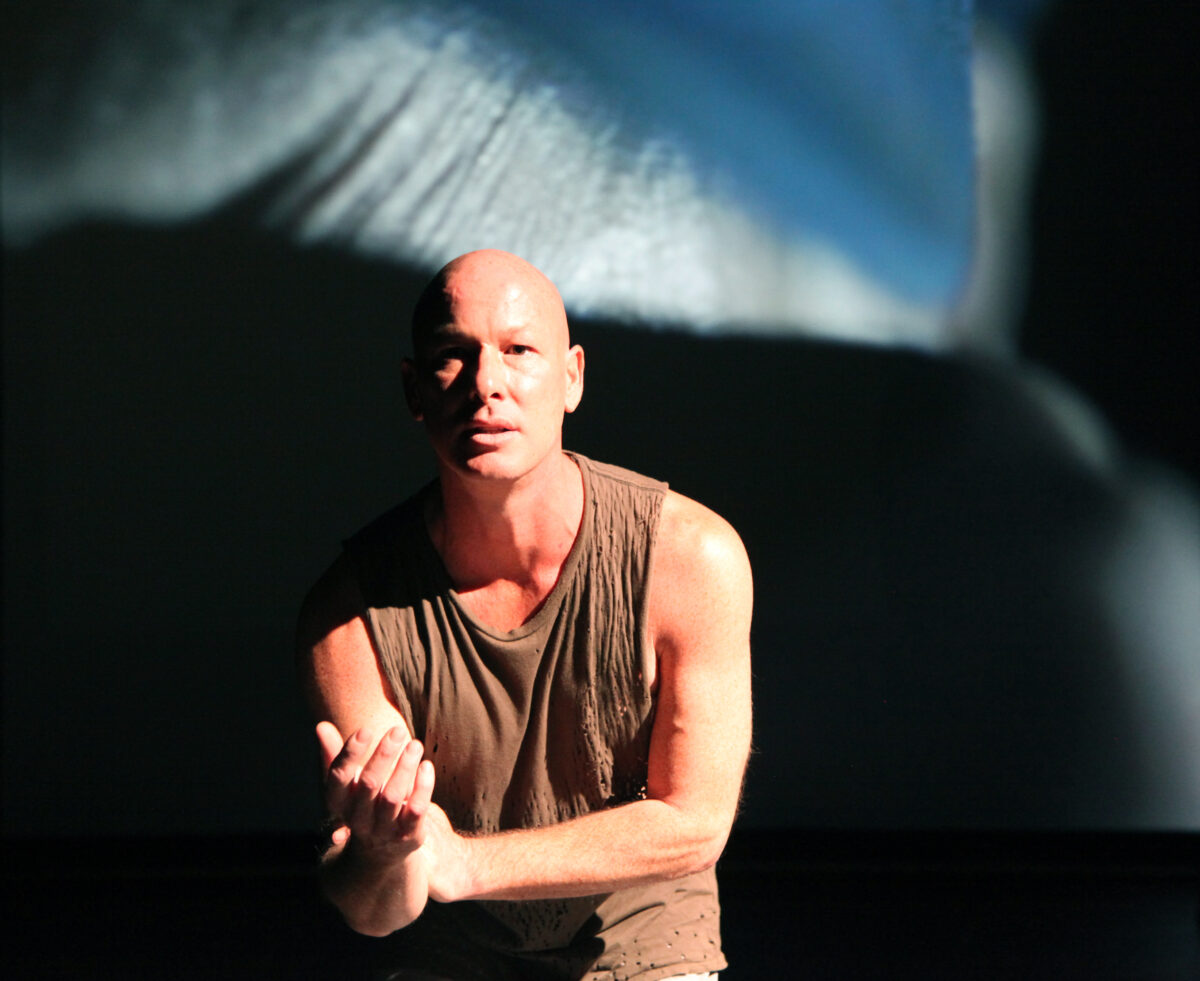

Jacob Boehme is a Narangga and Kaurna man from South Australia. He is a multi-disciplined artist with a background in dance, theatre, film and festivals (among other art forms). He has held many senior positions within the First Nations art industry for over two decades, with his most recent appointment as the Director of First Nations Programs at Carriageworks in Sydney.

In this dialogue with Tiwi producer Libby Collins, Jacob proposes a path of evolution for how we understand best practice in the arts – this begins with moving past an inherited system of transactional art-making and distribution towards trade systems influenced by traditional models and caring for Country.

What would you consider best practice in your field when developing engaging and approaching First Nations content?

This is a hard one. I’m at a point at the moment, where I’m questioning a whole bunch of stuff. I’m questioning our skin in the game – in the current industry, as it is. As it stands, to be quite frank, I feel that the industry that we’ve all bought into, follows a capitalist agenda. Which is the total antithesis of what our mobs’ value system is. It’s just two opposing systems and we keep trying to fit in like we’re still assimilating our cultural practices to fit in with this capitalist, creative economy.

I’m struggling to figure out why and how we talk about ‘best practice’, because it always sits within a certain paradigm. We’re always put up against this system that we’ve been brought into or that we have to buy into to survive.

‘Best practice’ is consultation with Elders. ‘Best practice’ is permission from the broader community. It is consultation. It is the project timelines that span years of critical, authentic and deep engagement in your material. ‘Best practice’ is all First Nations teams not succumbing to the Western lens. ‘Best practice’ is foregrounding and centering First Nations’ performance methodologies at the beginning and/or centre of your work, especially in performance art.

That’s what I think best practice is. But every time I think of it now, I just think: what are we doing? Because we consistently have to fit into somebody else’s agenda. No matter how far we’ve come, or how articulate who we are – we have to ask, “for whose benefit is this?”

This also applies to our own community. We need to be as strict about what ‘best practice’ means within our community as we are with what we expect outside of it. Where we can look around at works being created and tell whether the work was made for us. You can see things and know that they’re not made for our eyes. You can see they’re not made for our Aunties to have a yarn.

We need to think; ‘best practice’ for who? Then you can look at the lens and paradigm in which the artist is making it, because we have to be real whenever we make work. Whether it’s for visual arts or a theatre performance.

Understanding that the majority of your audience is going to be whitefullas – how does ‘best practice’ fit into that? I don’t know, sorry. I’m not coming up with many answers, just more questions. While they’re still running with this capitalist agenda, our values are always going to rub up against it.

No matter how much they try with the motherhood statements of ‘embedding First Nations’ – what’s missing is that First Nations peoples need to be at the centre of decision making, leading the agenda. It’s tricky because the industry actually doesn’t know how to work with us. The system is completely off.

Why do you think this is? Are you feeling this way now because of a culmination of years of having to deal with ‘rubbing against the system’? What was the turning point for you?

The turning point was actually because of institutional lateral violence, the apathy and the lack of real engagement that I experienced. I’m not sure if you’ve experienced this, but it’s like you’re going somewhere and it’s expected that you bring change with you. At first everyone’s excited for a while and then as soon as you start to point out and map out what the change needs to be – everyone is consumed by fear. Then, instead of questioning the systems and the structures that you’re pointing out as part of the problem – you become the problem, because you’re the mouthy, disgruntled black. So you become the problem and then the institutional violence begins.

On the flip side to that, I’m doing this project with my family, and just about a week or so ago I was back on Country and I was with our Senior Elders. They’re all in their 80s and early 90s. I’m doing recordings with them because we’re making a new work and turning the creation of the Yorke Peninsula into a blackfulla opera, using ceremonial song structures. I’m sitting there with my Elders, senior mob in their 80s and 90s and I think to myself, “this is my purpose. I need to spend my time with all the information and the knowledge that I’ve gathered in this other world, I need to spend my time with my community building something instead of wasting my energy.” I thought “I need to put my energy here because this is where my soul feels happy, my spirit feels happy.”

Every time I go back to the institution, I’m depleted and traumatised, banging my head against the wall. I’m constantly having to fight and it’s not our fight. You [the industry] have to do the work and prepare the ground for us to come in.

It seems being with your Elders in your community is where you’re at ease – is this kind of project something you’ve been trying to do for a while?

I’m at ease because I don’t have to fight a whole range of people to explain why we have to do things in a particular way, or why there is no timeline to this conversation, or that there is no time limit, there is no final draft – because they’re bits of information that will come when it’s ready for me to receive them. This has been in the works for about four years. We already did another project this year.

We did an exhibition about the Dingo Dreaming and how our Dingo connects. It starts down in South Australia and ends up at Mornington Island way. Yeah, so we did that and out of that project came this one, which we’ve been talking about for years. Being with those Elders that I just thought – this is a no-brainer.

Of course, I encourage the industry to create those positions and embed First Nation perspectives and voices, but be willing to listen to them and not just add to layers of virtue signalling.

And with all this in mind, how do you exhibit best practice in your work?

I think we need to start evolving what it means to exhibit best practice because one thing that we’ve inherited is a system of developing, producing, presenting, touring art, and it’s not our system.

It’s not our trade system. Our trade systems are very different. They’re based on kinship, on trade routes, on knowing Country and familial relationships. Relationships that continue beyond generations, continue beyond the individual. That’s what trade systems we come from but Industry trade systems are purely transactional and it’s all around the coin.

One of the things that I think, in terms of exhibiting future ‘best practice’ as caretakers and custodians of Country – we need to start looking at the current climate crisis as a real issue in how we start to exhibit ‘best practice’ in First Nations work, because we’re not doing that.

We’re still going about touring the world and doing anything we want and yet we’re supposed to be the caretakers and custodians of Country. We should be the ones leading new ways of ‘best practice’ that are gentle on the environment and respectful of Country.

We can do this by using all of our knowledge systems that tell us when to go hunt, when to go fish, when to collect plants for weaving, when to gather food, and where to go for ceremony. We depend on all of this knowledge. Our planet is in trouble and we’re contributing to it by wanting to continually exist in this transactional model of; create, produce, present and tour.

There has to be new models that go back to our old trade practices. It’s the international touring and the lugging of gear all across the world. It’s the lugging of people all across the world, all in an economic system that is continually ruining our Country.

What are the new ways then? How do you think we can be more gentle? How do we revive?

Well, what happens if we look at our trade routes and our Songlines as our new touring routes? It’s not just to provide language and culture to our art, but how do we revive a really old trade system? Revive our trade practices and trade routes?

It was everything we were doing prior to 230 years ago and it’s not as if we didn’t trade and travel internationally. We had trade relationships with Asia. Some of our Songlines can be found in Asia. They travelled up there because there was a different landmass. So we’ve always done international trade.

This last project that we did turned into the Wild Dog Exhibition, and part of that was working with First Nations Taiwanese mob, because they have a dingo or mountain dog, but the DNA is similar to our dingo. So it comes from our dingo and so when I started working with them on the work, we found that their creation stories and their songlines about the dingo or the Wild Dog for up in Taiwan start the same as ours. The dingo was a cheeky boy who told lies.

I think that’s the thing that we need to face and grapple with. I don’t know that it necessarily means staying here in this country, because people may fear that we stay too local and can’t go anywhere.

Well, no, that’s not what I’m suggesting. Our people do move – we move for ceremony, we move for trade, we move for a whole bunch of reasons. All that business. We’re not just stuck in one spot.

But I think we need to see what we gain if we go back to some of our old practices in the system that we’ve all bought into and I have to say, I’m well entrenched in it. It’s a system that I was brought up in. It’s a system that I inherited and know that, in terms of the arts, I’m trying to unlearn it because it’s just another form of assimilation.

So in terms of considering trade routes as a form of best practice in touring – examples of this best practice is everything that happened prior to 230 years ago.

Is there a time throughout your career, were you look back fondly and think that actually did work, in terms of best practice, from start to finish?

There are a couple, yes. I mean, I’ve been in the game now for 20 to 25 years or more so there’s a few experiences over that time.

I think as I’m getting older, and in the last couple of years now with my works like; Wild Dog, Blood on the Dancefloor. I think less about rushing towards an outcome. That’s not the driving factor. It’s actually, when you place process and relationships and people first – there’s an outcome later, of course.

When you’re working with whitefullas, producers, theatre companies, and presenting partners, they’re all looking at what’s going on and when it’s going to be ready. You end up having to work towards a deadline.

With my work Blood on the Dance Floor, a solo performance work that I did, took four years because that was investing in deep practice with all my collaborators. The same with Wild Dog, as that was working with the community for years. That’s when it works well.

Those relationships and that time spent getting to know people is important to the process.

When you referenced creating art nowadays as being transactional and fitting into this capitalist economy, how do you think funding rounds for projects inform this relationship?

Artists are expected to make work for less and less money: to produce the work, to administer the work, to present the work, to put an event manager on and still the artist is on the bottom of the ladder. The storyteller is still at the bottom of the pile. The whole system is bruised.

Do you think that in turn would also inform the quality and sentiment of the work being created?

Of course it does. It does. It can completely dictate what we as First Nations artists and communities make because we’re all playing for mostly white presenters who will buy the work, so you have to fit into their aesthetic or levels of understanding and education.

They’re coming to you with an aesthetic and a little bit of knowledge about you and your work and your culture, but essentially, you’re making work to fit their aesthetic and their understanding of how that’s going to engage with their audience, and how many tickets you’re going to sell.

Your work has to be received by a mainly non-Indigenous audience for them to make money off you so that’s going to affect how you make work.

It already shifts you away from Indigenous dramaturgy, Indigenous performance methodologies, anything cultural. Because then you’re going to have to interpret culture to fit into another lens. So somebody else can understand it. There are so many more considerations.

In your experience over the years, starting as an independent artist and then taking on the senior roles you’ve held later on, do you think there’s room for this system to improve?

I think in terms of awareness within the sector – there’s a hell of a lot more opportunity for blackfullas. Whether that be music, film, fashion, theatre, dance and whether that’s writing or directing there’s so many more opportunities. However, the management of those sectors are still generally, one dominant culture. Although, now we are seeing a rise in POC leadership which unexpectedly brings a whole range of questions around allyship

How do you overcome all of this?

The desire to overcome these issues has been around for ages. It always comes down to an argument about money and what people want. First Nations touring routes, First Nations managed performance and art spaces

But I suppose expectation and ambition as opposed to reality and economics are two very different things because it always comes down to: we’re here, we’ve all got the knowledge to do it, so what’s stopping us from doing it?

Project led by:

Supported by:

In partnership with:

![]()